The use of leaders’ images throughout history has always had a

multifaceted role. During the days of revolution, the masses, with

passion and fervor, seized upon their leaders’ portraits, raising

them high with slogans and ideals, crying out with their full

existence. Yet, as time passes, those same images o cially

displayed everywhere, from textbooks to city walls lose their

original essence. Their presence, their slogans, and their

accompanying ideals, even with exact repetition of the words, no

longer carry their true meaning.

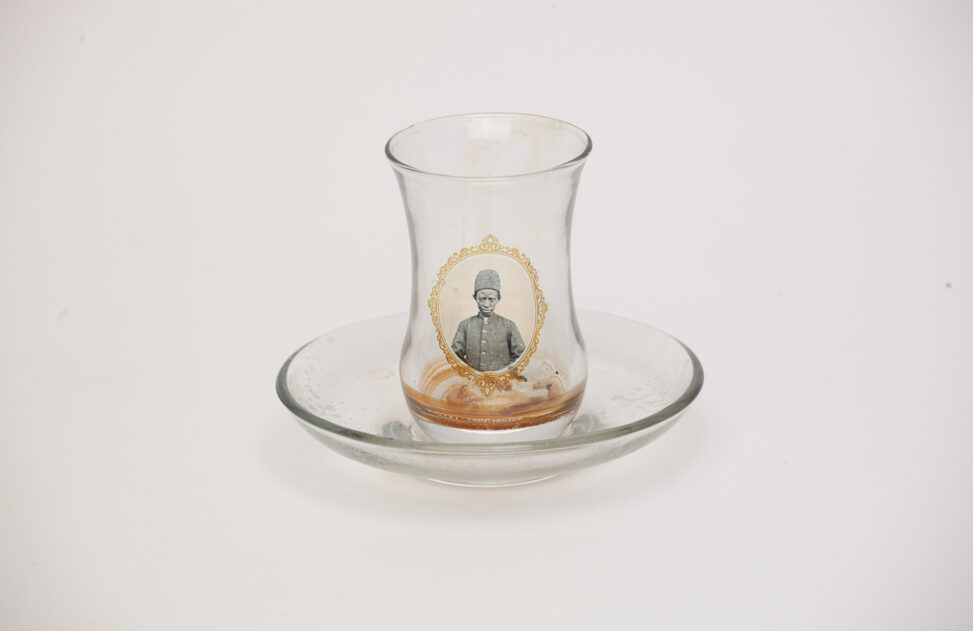

This complex relationship between image and power can also be

observed in modern Iranian history. Naser al-Din Shah was the

first to be photographed and brought this practice into the land.

Similarly, many world leaders had a special interest in recording

and multiplying their portraits. What is striking here, however, is

that despite the generally negative perception of his reign, his

images have endured up to today commonly used and even

carved onto small amulets turning his portrait into a beloved

token of devotion.

Leave a Reply